2018 Award Winner Interviews

Short Work Competition for Poetry

Lee Sharkey

Who is your first reader when you finish a new poem?

My first reader is almost always my friend Martha Collins. In addition to being a wonderful poet who has spent decades refining her craft, she has a sharp intelligence and an ear honed by musical training. I can trust that she will understand my intentions for a given poem (we have been reading each other’s drafts for several years) but nonetheless be unflinching in her critique of it. Very little gets past her, and I’m grateful for that.

How has working as an editor influenced your own writing?

I’ve been editing since I joined the staff of my high school literary magazine in 1961. I can’t seem to escape it. More recently, I stepped down from the editorial board of the Beloit Poetry Journal after thirty-one years. Editing is a time-consuming but effective way to learn poetic craft: if something in another person’s poem makes you wince, you learn to watch out for that tendency in your own writing. BPJeditors often work closely with poets on revisions of their poems. Homing in on a poem’s particulars, down to the choice of articles, articulating your concerns to the poet and persisting in conversation until you both feel you’ve got it right, is instructive—not to mention rewarding. More generally, the constant exposure to freshly-minted poetry invites the imagination to explore new domains and open to new poetic strategies.

You’re the literary editor for Doors, a collection of visual art and poetry by adults recovering from mental illness. Can you speak to the role of poetry in the process of recovering from mental illness?

Language that both speaks and listens, attentive to tone and intent, can be transformative. It bypasses the ego and effects change in the body—both the speaker/author’s and the reader/listener’s—on a neuromuscular scale. Healing from personal or collective trauma is a long-term process that requires continual renewal of commitment; in a supportive environment, writing from a place of personal truth can inspire us to renewed courage and compassion. In three decades of teaching creative writing to adults with mental illness, I have been privileged to watch this process unfold for a long line of people who claimed power over their lives by listening to and shaping their wholehearted voices.

Book Award for Anthology

3 Nation Anthology

Valerie Lawson (Editor)

(Resolute Bear Press)

What inspired you to launch this project?

When my husband, Michael Brown, and I moved to Maine eleven years ago, we were drawn to the area around Passamaquoddy Bay. We liked being near Canada, and the Passamaquoddy Tribe in Sipayik and Motahkomikuk.

The 3 Nations Anthology was conceived in a much more hopeful time. The nationalistic tone of the new administration made the call for dialogue among neighboring nations all the more critical. There are no arguments here, just neighbors writing about relationships, heritage, and the land they love and share. This book was meant to build bridges, not walls.

What does community mean to you?

Community is one of those warm and encompassing words. A few years ago, I participated in a community project to build a birch bark canoe with Master Passamaquoddy artisan, David Moses Bridges. Over the course of two weeks, David coordinated a group of eager people at all skill levels in a monumental undertaking as cedar, birch bark, and spruce roots were fashioned into an ocean-going birch bark canoe.

A community was built along with the canoe. Great things happen when people gather with purpose. Through this project friendships were built and a treasured craft and tradition was passed on. It has been heartening seeing the authors in 3 Nations Anthology get to know each other at readings, to share their stories and their lives, and create another community.

What was your selection process for this anthology?

While selecting pieces for the anthology, I looked for real connections to the region, not drive-by missives from people who visited for the first time and felt compelled to write something up. The list of “starter” topics in the submission call turned out to be helpful, many of the pieces fell broadly into categories like food, heritage industries, landscape, geography, and nature in general.

The very first piece to arrive was “Borderline” by Stephanie Gough from Campobello Island, New Brunswick. The piece is about living in a hybrid zone on a Canadian island connected by bridge to the United States. The border crossing is a part of life in a place where you have to cross the border to shop, gas up your car, or go to a bar. “Borderline” is filled with This Is Us moments for the people who live here.

In the end, the pieces in the book seemed to select themselves. It seemed everyone already knew each other and were simply waiting for the invitation to come in and strike up a conversation with their neighbors.

Excellence in Publishing

There Has to Be Magic

Donna Marie McNeil with Christina Shipps

(Maine Authors Publishing)

What sort of challenges did you find in There Has to Be Magic’s production and how did you navigate them to create an award-winning book?

Jane Karker, Maine Authors Publishing: For almost every book project that comes our way, Maine Authors Publishing has three priorities in the beginning of a project: The first priority is to do a proper editorial evaluation and perform professional editing and proofreading for each and every book that falls under our imprint. The second priority is to keep the project affordable for the author. The third is to listen carefully to exactly what the author wants. Our three top priorities, starting from the beginning, are often at odds with one another; keeping that balance is always the biggest challenge.

There Has To Be Magic broke all of our usual molds. This project was different in many ways. For one thing, this is the first book we have ever produced that was fully edited and proofread before we received it. We quite often hear that “the editing is done” from new and inexperienced authors, but we soon discover during our editorial evaluation that it is not, or at least not to our standards. Then we start the long journey of explaining the need for and expense of proper editing.

The more experienced the writer, the more accepting they are of editing process, and many of our seasoned authors relish the process. In the case of this amazing book, authors Donna Marie McNeil and Christina Shipps really meant what they said, and we received an immaculate manuscript.

This book was also set apart from most of our projects because the authors were more open to expensive printing options. As a printer by trade, my role at Maine Authors Publishing is to advise how to keep the cost of printing down, so reorienting my prudent nature to allow for and celebrate a few more “bells and whistles” in the printing and production of this book was liberating. It did take some adjusting for me. But after all, sometimes there simply has to be magic!

You’re a yoga instructor and a writer. Do you find a relationship between the two practices?

Donna Marie McNeil, co-author: Ah Ha, that feels a little confining. Having lived a long life, I’m a culmination of many things: artist, gallerist, museum director, dance company director, arts agency director, foundation director, fashion hound, foodie, swimmer, but centrally my professional life is grounded in arts administration and arts advocacy with my training and passion in studio arts and art history. My yoga practice came along in the middle of my professional career, grounding me, strengthening mind, body and spirit — it’s a genuine tag line — and the practice is for me, transcendant. The asana practice, wriggling out the physical knots, prepared me for the meditative practice and together render calm, reflection and patience. That enmeshed with a highly trained aesthetic, were great guides as I approached my love of words; the transformative magic and beauty of them written, spoken and sung.

How has your background in visual art influenced your writing?

Donna Marie McNeil, co-author: All my public writing has been about artists and art work. Beginning with short essays and funnily enough, grant writing, and growing into longer commissioned pieces. I feel that my training as a maker deeply rooted in the principles of aesthetics, informs and transfers to my efforts on the page. I am interested in artists as seekers and I’m interested in the transformative power of words juxtaposed on a page as descriptors, metaphors and pathways to new thinking, functioning much like all art forms. The movement in contemporary art work to cross fertilize and enfold disciplines speaks directly to your question that creativity can and does flow between and among ways of expression, so yes, absolutely, I could not have written such a book without my deep and multi faceted engagement in the arts. Beauty transcends any particular application and once rooted deeply inside it informs all your activities.

John N. Cole Award for Maine: Themed Nonfiction

One Man’s Maine

Jim Krosschell

(Green Writers Press)

Do you have a favorite spot in Maine?

Favorite spot. The problem with Maine is that the place I’m in at present tends to be my favorite spot, until I move a few miles and then that’s my favorite. We also have the big-state problem: there are places you see a lot and places you get to see only occasionally. If I must pin down favorites, let me choose in the former category the view from Beech Hill in Rockport (a Coastal Mountains Land Trust preserve), and in the latter, Quoddy Head State Park in Lubec.

OK, so these are not problems; they are blessings.

Your book explores Maine’s changing ecology while presenting hope for the state’s future despite climate change. What is something you’d like for readers to take away from One Man’s Maine?

Take-aways. I hope readers take away an appreciation not only of the incredible variety of natural wonders in this state, but also a sense that humans here can and do live in a right relationship with nature. Maine offers the chance to balance a life. Wherever you live, whatever you do for a living, whether you’re a resident, a tourist-in-residence, or a visitor, a kinship with bird or surf is just a few minutes away. Maine makes it obvious that we ignore our roots in nature at our peril.

The mission of the land trust for which I volunteer is that we permanently conserve land to benefit the human and natural communities of western Penobscot Bay. In a way, my book’s mission is to extend that to the whole state. And farther: Maine is an example to the world of how to do things right.

The title of One Man’s Maine is in conversation with E.B. White’s One Man’s Meat. Did White’s collection of essays have any other influence over your book?

E.B. White is a hero of mine; hence the dedication in my book: “In homage to E.B. White, whose delight in the ordinary, compassion in the face of chaos, and comfort in his own skin can only be imitated, never equaled.”

I re-read One Man’s Meat every few years, and every time I laugh and cry all over again. That book is the reason why, some ten years ago, I started to write personal essays about Maine.

Youth Competition for Fiction

Makena Deveraux

Would you like to pursue a career in writing?

I have written short stories and poetry for as long as I can remember, but I had never wanted to pursue a career in writing. I think because I merely saw it as a hobby. Yet, recently as the writing world has opened up for me and I’ve started to take it more seriously, I definitely want writing to be a part of my career in some way. My dream right now is to be a screen writer for movies but I’m also really interested in anthropology.

Do you have a favorite book or author? If so, why?

My favorite author is definitely Ray Bradbury. His writing has been very influential for me and in helping me develop my writing style as a young adult. His stories are full of the most beautiful figurative language and have some of the most intriguing plots I have ever read and you can just tell he has a connection to each and every word he has written. There’s something about his writing that causes your imagination to run wild and I greatly value him for that.

You were a finalist for both poetry and fiction. Do you prefer writing one over the other?

I have always appreciated both fiction and poetry equally, but as a kid I predominantly wrote fiction, I think mainly because that’s mostly what I read. Yet, as a teenager I find I’m mostly writing poetry. It seems so much more explorative and limitless I suppose, like I don’t have to follow certain guidelines like I sometimes feel I have to when writing fiction. But to answer the question, I don’t really prefer writing one over the other, I just have found myself exploring each in different ways at different stages in my life.

You recently co-wrote an opera! What inspired you to do so?

I am constantly exploring new forms and styles of writing, so when I came across the opportunity to co-write an opera libretto I thought it would be an incredible experience to work with other teen writers and, at the same time, make a wonderful piece of art. I saw the opera as a way to make a statement through a platform historically dominated by adults, which is exactly what the opera “Girl in Six Beats” ended up doing.

Book Award for Young People’s Literature

GRIT

Gillian French

(HarperTeen)

What led you to write young people’s literature?

Books were such a vital part of my journey through young adulthood, a port in the storm during those tumultuous teen years. My parents instilled in me a love of reading at a young age, and I always knew that I wanted to become a writer—but my need to escape the often brutal reality of middle and high school helped me target my core audience. Coming of age is endlessly fascinating to me; through all the ups and downs and rapid-fire changes, you find out who you will become, what truly matters to you. You choose your own path. Depicting a young person’s struggle to assemble a moral compass against great odds will always be my favorite challenge as a writer.

Do you think YA books are increasingly tackling current social and political issues?

YA fiction has long been characterized as issue-heavy, stories illuminating universal teen rites of passage such as sexual exploration and drug experimentation. In recent decades, authors have found a way to work in more hot-button, ripped-from-the-headlines themes as well, which I think is fantastic. Right now, teens are caught in the same current of violence, bigotry, and hate as the rest of the country, and I think they’re looking everywhere for guidance. YA and children’s authors have a unique opportunity to shed light on those dark and frightening topics, to be the trusted source young readers turn to.

What’s something you want the reader to take away from GRIT?

GRIT is all about self-discovery, about breaking free from the judgements of others and finding your true path. I think it’s easy to fall into a black-and-white mindset, to judge another person by their surface and look no deeper; I’m guilty of it myself. But a rigid worldview allows painful secrets and hidden abuses to thrive, especially in small communities. I hope this story challenges the reader to always question, consider, and be generous with second chances.

Book Award for Crime Fiction

In Solo Time

Richard J. Cass

(Encircle Publications)

Have you always had a passion for crime novels?

I started out writing short literary fiction and saw that the stories I wanted to tell weren’t falling into places the more literary markets were interested in. I’d always read crime novels, from the Hardy Boys when I was young, through Alfred Hitchcock and Rod Serling, and then into the great pulp writers of the 60s and 70s: John D. MacDonald, Charles Willeford, Donald Westlake. Once I realized that crime novels made up a huge proportion of my reading, it was an easy jump to start thinking I might want to write one. And, too, the genre has evolved over the last half century so that it is no stretch to call some of the best crime fiction being written today as good as the more literary work. People look down their noses less at genre novels than they did once. And people read them 😉

Where do you go to seek inspiration for your writing?

When I’m not actively working on a project, I spend a lot of time outdoors: fishing, hiking, snowshoeing in winter. I find the combination of nature, air, and exercise is probably the most useful way to get new ideas moving around. That said, I am also a great fan of the little filler articles that sometimes appear in the newspaper and on the Internet that highlight some odd occurrence or strange character. My experience tells me a good idea can come from almost anywhere. I try to keep my eyes and ears open to possibilities, but especially the offbeat and weird.

When beginning a new project, what comes to you first: the crime or the criminal?

Most often, the very beginning of a project for me has to do with a character–it might be a criminal, it might be a bystander. It has to be someone I’m interested in and who seems like he or she has a story to tell. I noodle around, trying to understand the character. Once I have a basic grasp of this person, who I hope at this stage is big enough to carry a novel, I start probing the character to see whether he or she is a victim of a crime, a criminal, and also what the character’s central conflict, which will drive the story, has to be. Though this all sounds very methodical, it definitely isn’t a conscious process. But mainly, the character I get interested in writing about usually drives the sort of crime that ensues.

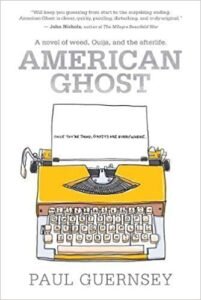

Book Award for Speculative Fiction

American Ghost

Paul Guernsey

(Talos)

American Ghost isn’t your average ghost story. Where did you get your inspiration for the tale?

At the time I began imagining American Ghost, I was at a crossroads in my life, and perhaps second-guessing some of the decisions I’d made. I was also doing a lot of rambling in the Maine woods, where I would sometimes come upon overgrown cemeteries full of people who’d been gone and forgotten for many decades. I wondered what those people would say if they could talk to me, and before long I realized that I needed to write a ghost story on the themes of regret and redemption—regret, after all, being what a ghost is all about. Then, one by one an array of colorful characters began materializing—ghost-like, you might say—from different periods of my past: bikers, lost souls, Venezuelan gangsters, backwoods folks, druggies, people whose vibrant lives had been cut short, bitter novelists who ended up doing things like raising pigs instead of writing. . . .

Do you have a favorite ghost story?

I’ll give you two, one classic, one contemporary. Henry James’ 1898 novella, The Turn of the Screw, not only is a terrifying ghost story, but a great work of literature in any genre. The story delves into aspects of the human psyche—chief among them sexual repression—that psychoanalysts including Freud had not yet even described at the time it was published. The other is “The Donegal Suite,” by Lisa Taddeo, which is part of an anthology I’m currently editing for Wyrd Harvest Press called 21st Century Ghost Stories. I think this short story is a tour de force, combining as it does a gripping ghost yarn, caustic (and multi-national) social commentary, humor, and a distinctive literary style.

What makes a ghost story truly chilling?

The ghosts aren’t the scariest part of a ghost story—it’s how the living characters react to the ghosts that is truly chilling (think of the protagonist’s descent into madness in Stephen King’s The Shining). A ghost story is most effective when it illuminates one of the darker, colder corners of the human mind—and reveals uncomfortable truths about who and what we are both as individuals, and as a species.

Drama Award

Michael Burke

What inspired you to step away from nonfiction and environmental writing and towards playwriting? What were your biggest challenges in tackling a different genre?

I think I was mostly inspired by the experience of going to Wilton’s town meeting many times over the years, and realizing eventually what a drama– of a certain sort – unfolds there. Town meetings have all the requirements of drama: characters, conflict, tension and resolution, and a surface topic beneath which other subjects lurk.

So I found the experience a good one for turning into a play, and as a writing experience, I found writing dialogue liberating – no, or very little, exposition! In reading and attending plays, I think I gradually came to appreciate the power of the simplicity of a play: characters’ words and actions in regard to one another. That’s powerful, and fun to write, especially as a novice playwright. It’s a much different imaginative experience, to write a play rather than prose, than I would have thought before I gave it a try.

What advice do you give your students about writing?

I give them plenty of advice, more than they want! In my creative nonfiction classes, I focus on helping them understand what the tools of nonfiction are, the devices, and how to employ them. Quite often they’ve seen the tools used on the page, they’ve witnessed them being put into action, but they need to have the craft elements named, and called to their attention, and they need suggestions on how they might use this or that tool on this or that occasion.

I also set out some principles, especially about honesty, truth, and vulnerability in nonfiction. One of those principles is that the writer has absolute authority to choose whatever story he or she wants to tell, but whatever they choose, they have to be willing to be honest about it. This comes up a lot when someone writes about a difficult or sensitive topic; they don’t have to write about it, but if they choose to, they have to go all the way, not hold back.

I also advise them to take risks, even if the result doesn’t work out. That’s hard for students to hear, because of course they are eventually graded, and they care too much about grades.

When you’re not teaching or writing, what do you enjoy doing most?

As the owner of an old house in Maine, I spend a lot of time working on it; I’m not sure that counts as enjoyment. But other than that, my wife and I like being in Europe, perhaps at an artist residency, and we have a camp nearby, where I like to swim and float on an old air mattress. I still like to run for exercise, competing occasionally in 5Ks and 10Ks, and to bike and use Colby’s gym. I try to stay up to date on environmental literature, ecocriticism, and the environmental humanities. I also spend a lot of time fuming about politics and the fate of the country.

Book Award for Fiction

A Piece of the World

Christina Baker Kline

(Harper Collins)

What inspired you to write about the painting Christina’s World?

When I was writing Orphan Train I immersed myself in the literature and history of early-to-mid 20th-century America. I became particularly interested in Depression Era rural life — how people got by, and what emotional and mental tools they needed to survive hard times. After I finished that novel, a writer friend remarked that she’d recently seen the painting “Christina’s World” at the Museum of Modern Art, and for some reason — my name? the connection to Maine? — it made her think of me. Instantly I knew I’d found my subject.

My family moved to Maine when I was six; my parents were determined to show me and my three sisters everything the state had to offer. Among other adventures, we visited the Olson House in Cushing, where Christina’s World was painted. (I wrote about this excursion for The New York Times.) Also — my mother, grandmother and I are all named Christina; my grandmother grew up in the same time period as, and in circumstances similar to, Christina Olson. But I’m not sure I would’ve found this subject if I hadn’t had that chance conversation with a friend.

Do you believe there is a strong connection between the literary and visual arts?

For me, there certainly is. When I teach, I often use visual writing prompts. When I began writing A Piece of the World, I worried that I would get sick of Christina’s World, but I never did. Wyeth’s art is endlessly fascinating to me. For decades, critics derided his work as simply, dully, representational — paint-by-numbers and uninspired. But recently art historians, curators, and critics are coming to see him differently: his work is now described as “metaphoric realism” or “figurative surrealism,” in which the ordinary is heightened to reveal fundamental aspects of human existence. I can still look at Christina’s World and find new things to consider in it.

You’ve lived in many places throughout your life—what inspires you to continue telling Maine-based stories?

Though both of my parents are Southern, and I was born in England and lived there as a child, we passionately embraced our adopted state. I’m not naïve enough to consider myself a Mainer (though two of my younger sisters can, perhaps, having been born and raised here) – but I did spend my formative years in Bangor. Now I’m lucky enough to write and live part time in Southwest Harbor; my three boys consider it home. For me, it’s as simple as this: Maine is where my heart is.

My novel Desire Lines was set in Bangor, a place I knew intimately. I created a fictional Maine town, Spruce Harbor, in my novel The Way Life Should Be. I also set Orphan Train there. I wanted to write about Mount Desert Island because I’m here so often (and so much of my family comes here too), but I realized that I’d have a lot more freedom if I created a fictional village. In my mind, Spruce Harbor is sort of like Platform 9 3/4 in the Harry Potter books, a mythical little sliver that exists between real places. It’s mine to imagine.

Short Works Competition for Fiction

“The Detective”

Zach Brockhouse

Where do you go for inspiration when beginning a new piece of fiction?

I have two young children, so there is no real safe space for inspiration. Exhaustion leads to some interesting places sometimes. I find music usually does the trick. Then I ease up to the dining room table after everyone else is asleep and work it out.

What’s your favorite genre?

It feels strange to pigeon-hole this as a separate genre, but I love southern fiction – Mark Richard, Barry Hannah, William Gay, Larry Brown, Flannery O’Connor…

Your website notes that you enjoy local food and brews. Where is your favorite place to eat in Maine?

I’m not much of a foodie. I know what I like, though. I find nothing more satisfying than sitting at the bar of The Thirsty Pig in Portland, savoring something from Maine Beer Company and having a chili dog with yellow mustard and raw onions.

Book Award for Children’s

Pocket Full of Colors

Jacqueline Tourville

(Simon & Schuster)

What’s your favorite Disney movie?

I am a huge fan of Disney short films from the 1940s and 50s—”shorts” that were played before the main feature film. Because there was less on the line, Disney studios generally allowed more risk taking and experimentation with how these were animated. My favorite is Once Upon a Wintertime (1948), a short about a romantic date on a frozen pond that goes very, very wrong before reaching a quintessential Disney ending. Mary Blair served as art director and her style and artistry really shine through! My favorite Disney feature film is Bedknobs and Broomsticks. I love the mix of live action and animation!

What’s the hardest part about writing a children’s book?

As an author of picture books—and not an illustrator—I am constantly reminding myself to leave room for the illustrator to have his/her own creative fun with the story. When editing, I focus on finding (and deleting) adjectives that would needlessly pigeonhole illustrations. Does it really need to be “red” barn? Understanding what words absolutely need to be in the text, and what can be left to the pictures is often a tricky balance—and part of the alchemy of picture books. I generally don’t worry about this when writing the first drafts, but when I edit, part of polishing is understanding how to pare down the text so that it’s ready for an illustrator’s magic touch. When the book comes back with the first round of illustrations, the text might change again when we see how the pictures tell part of the story. For example, there was an entire last paragraph of Pocket Full of Colors that was chopped once we realized Brigette Barrager’s amazing final spread already said everything we wanted to—and more!

What was the most inspiring thing you learned when researching Mary Blair?

Mary Blair was one of the first women to join the inner sanctum of Walt Disney Studio’s animation team. During her time working with the “Nine Old Men,” the nickname for Disney’s core group of animators, Mary’s work was frequently rejected as too colorful, too modern, and too bold. Instead of giving in the demands of her bosses that she conform to the dominant look and feel of Disney movies at the time, Mary stuck to her colorful vision—and now her work is viewed as a high point of Disney’s golden age. She worked on such films as Alice in Wonderland, Cinderella and Peter Pan, and the It’s a Small World ride at Disney is pure Mary Blair. One interesting thing I learned in researching the book is that Walt Disney loved her work so much that one of Mary’s paintings was the only art he ever had on display in his office.

Youth Award for Nonfiction

“Online and Offline”

Ayub Mohamud

What’s your favorite class or subject in school?

For me my favorite subject in high school was History. I enjoyed history because I felt like a story was being told every time I went to class regardless of the teacher. This made me actually look forward to going to classes. Which I really never felt for other subjects.

What’s your favorite sub-Reddit? Why?

I have a lot of favorite subreddits, but If I were to narrow it down to 1 or 2 it would r/globaloffensive or r/nba. I browse those subreddits the most because those are my 2 favorite hobbies. Basketball and playing counterstrike. There’s also that community factor to being apart of those subreddits (even thought there is 500,000+ subscribers)

“Online and Offline” explores how you navigate your many identities—particularly through the Internet and gaming world. What role does writing play in navigating your identities and becoming the one Ayub you speak about at the end of the piece?

I feel like writing for me especially online has helped me have a place to vent to that I previously didn’t have. I get to have more social interactions online then I ever did before using the Internet. I feel like helped form my current identity.

Where do you hope to be in five years?

Honestly, I don’t know. I was hoping with me graduating from high school last year that would help clear me from confusion, but its actually gotten worse. Hopefully in the next five years I don’t have that uncertainty anymore.

How has completing The Telling Room’s Young Writers & Leaders program shaped your writing?

The Telling Room’s YWL program helped me navigate first what an Identity was and how it shaped me into being who I am today. It also gave me a new perspective since I had alot of diversity and diffrent people participate in the YWL. It also helped that I had mentor that kept constantly pushing me to go more in depth into my thoughts and not just give generic 1 to 2 sentence answers.

Book Award for Poetry

Work by Bloodlight

Julia Bouwsma

(Cider Press Review)

Have you always wanted to be a poet?

I’ve been interested in language and in stories for as long as I can remember, was the weirdo kid who kept a copy of Dante’s Inferno in my locker, but I think the deal was sealed when I was in the third grade. A family friend and poet volunteered at my school as a poetry teacher. Once a week she met with any students who wanted to participate and taught us poetry. We read Blake, Hopkins, Yeats, Dickinson, Frost, Keats. We wrote our own poems. I wanted to end each of my poems with the word “eternity.” She convinced me, kindly but persistently, to give this up, and eventually I did. That was when I first committed to the necessities of revision, so I guess it marks the moment I committed to becoming a poet.

What advice would you give someone who wants to start writing poetry?

Keep writing. Read as widely and as much as you possibly can. Don’t be afraid to experiment, take risks, make mistakes. Make some poetry friends who can give you a second set of eyes on a poem, suggest books you wouldn’t have thought of reading on your own, and offer you moral support when it comes to submitting your work and weathering the inevitable rejection. Know that writing poetry is deeply lonely and difficult work. It’s deeply rewarding work too. Build a rich life for yourself to help counter the hardship. If you’re writing well, it should hurt a little. And don’t give up even when you aren’t writing well—we all go through it. Don’t give in to self-loathing or fear. Keep practicing, keep learning, stay humble, stay curious. You’ll always be a student. Poetry is lifework. Know that the world needs you.

What’s it like to be a farmer and a writer? How does farming influence your writing, and vice versa?

Farming is quite literally grounding. With my fists buried in the earth planting seeds, with my hands gaumed up with smashed potato bugs and juice from the tomato vines, with my arms full of firewood, I have a direct connection to the world around me. When you raise animals, you experience life and death firsthand. You remember that we’re all just animals in the end. The work of farming is directly tied to the work of living. This helps me remember what matters and keeps me tethered in the world so I can let my head go, my mind wander in search of language, which furthers my desire to work—what Wendell Berry means in The Mad Farmer Poems when he writes that “thought passes along the row ends like a mole.” I’ve developed an intimate relationship with my land which now shows up in nearly everything I write. I’ve come to think of poems as places within places—topographies and terrains built simultaneously through the work of the hands and the work of the heart.

Book Award for Nonfiction

The Evangelicals

Frances Fitzgerald

(Simon & Schuster)

What do you think is the role of a nonfiction writer in this modern moment?

I can only say that journalism has a role to play in reporting the truth.

As a journalist, what was the most compelling story you followed?

My first answer must be the Vietnam War. However, that’s very broad. If you’re asking for one discreet story, I think it would be my attempt to winkle out the truth about the Rajneeshi sect in Oregon. (There’s a documentary about it now called “Wild, Wild Country.”)

If you could live in any time in American history, when would it be?

I would like to have lived in the Progressive period at the beginning of the 20th century, when Teddy Roosevelt and others were redressing the ills of the late 19th century, and it seemed that anything was possible.

Short Works Competition for Nonfiction

Leslie Moore

What’s your favorite animal?

Dogs! I’ve loved and lived with dogs my whole life. Eight of them—a black Lab, two golden retrievers, a West Highland white terrier, a Scottie, and three small mixed breeds. Rumi, my current dog, a cockapoo, takes his job as artist’s/writer’s muse seriously. He’d quite happily spend every waking and sleeping minute of his life amusing me. I’ve also spent the last 20 years drawing pen-&-ink dog portraits. This is not to say that I don’t love other furry, feathered, and finned creatures. Most of my writing and art is animal centric.

Do you find a relationship between your visual and literary art?

My pen-and-ink drawings are detailed and realistic. I suppose my writing is too. However, I also practice relief printmaking and it’s much more unpredictable, playful, and suggestive. I hope this practice influences my writing as well. Recently I’ve been writing a lot of poems about animals and I don’t have to dig deep to find the artwork to go with them.

Do you have any writing or artistic rituals?

I don’t have rituals so much as compulsions. ASD: Attention Surplus Disorder. While I’m working on a piece of art or writing, I’m lost to it. I’ve always loved Willa Cather’s definition of happiness: “. . . to be dissolved into something complete and great.” I dissolve into making marks on paper–drawing, printmaking, writing. When I get an idea, it’s full steam ahead, without looking left or right. This has its drawbacks. I’ve let tea kettles boil dry, wood stoves grow cold, and my neck muscles twist into knots. This is where Rumi, my dog/muse, comes in. He has rituals if I don’t, and they demand that the two of us get out of the studio/study and into the exciting world of racy smells–the park, the beach, the Harbor Walk, the Rail Trail, even just around the block. He checks his pee-mail and I find the right words for a troublesome poem or the solution to a tricky printing problem. So, back to the question: dog walking is my creative ritual.

Book Award for Memoir

Redeeming Ruth: Everything Life Takes, Love Restores

Meadow Merrill

(Hendrickson Publishers)

As someone who previously wrote kid lit, what was the biggest challenge in writing a memoir?

Curiously, having attended children’s writing workshops and writing a yet-to- be published middle-grade novel helped me find the structure, description, character development and dialogue to write my memoir. The same III Act Structure with its triggering events, turning points and resolution that helped me shape my novel, helped me shape my memoir. On some levels, I am a slow learner. So the simpler I can make something, the better I understand it. That’s one reason I write for children! The biggest challenge in writing memoir, however, was deciding which parts of Ruth’s story to leave in and which to leave out. Because I’d lived it, what was important to me wasn’t always the same as what was important to the story. Thankfully, I had a great local writers group for support and feedback!

As you were drafting Redeeming Ruth, what did you learn about Ruth, your family, yourself?

That we are not exempt from pain and loss. I grew up in a Christian home and church that encouraged us to live lives motivated by love and service. Somewhere along the line, I grew to believe that if we did, we could avoid suffering—as if God would give us a “Get out of Jail Free” card for good behavior. Instead, what I discovered, particularly while writing Ruth’s story, was that the greater you love and the more you serve, the higher the likelihood that you will suffer. But as I wrote Ruth’s story—and saw the impossible situations that she and we had overcome—I also discovered that God is faithful and desires to walk through the pain and loss with us.

Where is your favorite place to write?

Anywhere with my door closed. We live in a small house with five kids, ages 21 to 5—another reason I write for children! My current office is our laundry room. If I save our laundry (something else we have a lot of) for when I sit down to write, the whoosh and whirrr of the washer and dryer blocks out all the noise and chaos.